Health in India’s Urban Slums: Addressing the Triple Barrier of Space, Stigma, & Systems

India’s urban cities are growing, shining brighter with every passing day. New hospitals, healthtech startups, and medical innovations are popping up everywhere. You hear about robotic surgeries, app-based consultations, and world-class ICUs making headlines. But there’s one side of these modern cities that barely gets a mention. A part that isn’t Instagrammable, isn’t spoken of in coffee-table conversations, and definitely doesn’t make it to the glossy brochures about India’s urban progress.

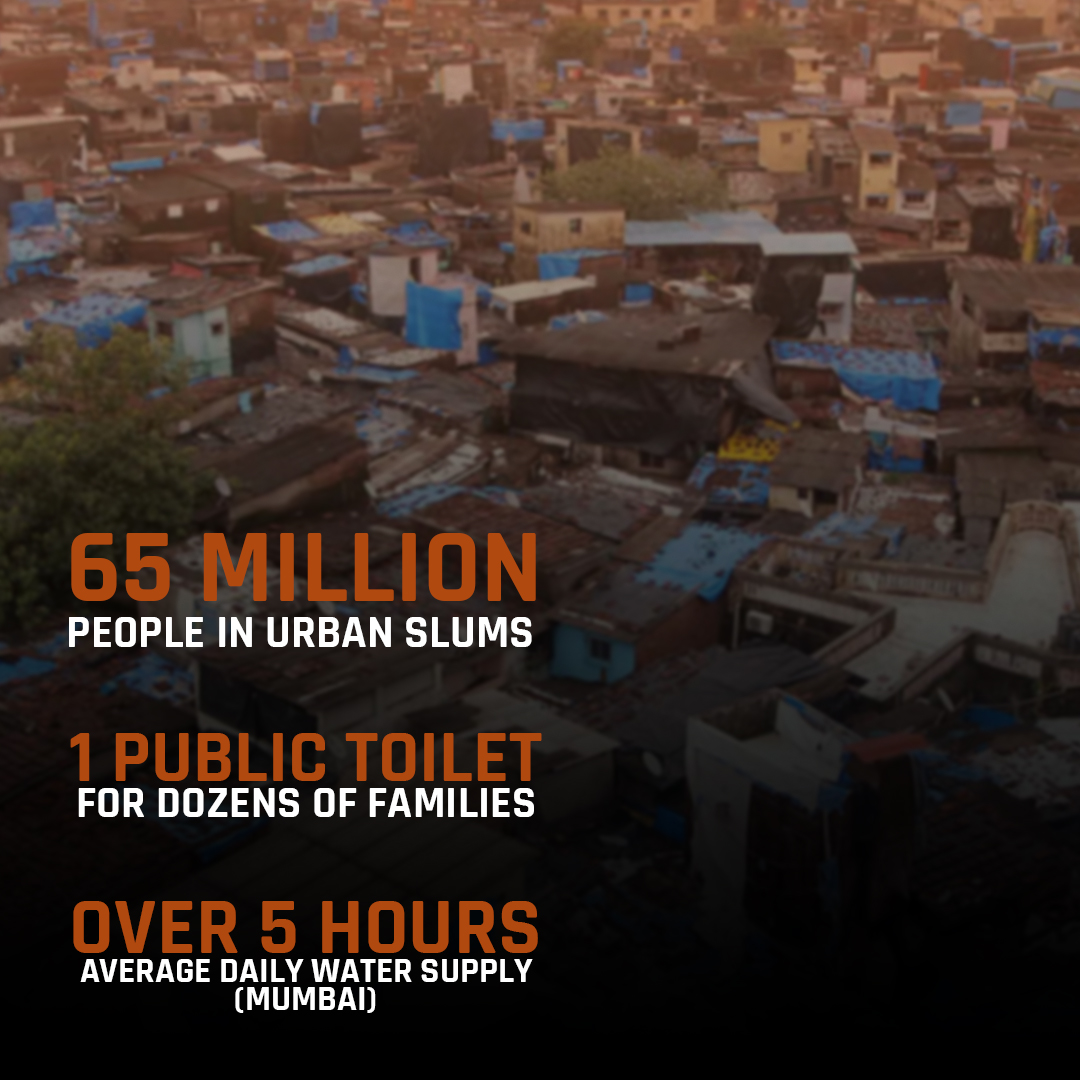

Yes, the slums! Home to nearly 65 million people, cramped into narrow lanes, makeshift homes, and spaces where even basic necessities like clean drinking water and sanitation are a luxury. Forget high-tech hospitals, some of these places still struggle to get a reliable supply of electricity and safe toilets.

Two Indias: One City, Two Realities.

We, sitting in our urban homes, often believe healthcare in cities is miles ahead of rural India (and if you haven’t read my other two pieces on urban vs. rural healthcare and the big question mark around health equity in India, I highly recommend you do before you dive deeper here), there’s a whole section within these cities that remains invisible. Unwanted, less shiny, and quite conveniently ignored.

Why is this part left behind? Why do millions still lack even the most basic healthcare in cities bursting with medical advancements? Honestly, it’s a question neither you nor I can answer completely. But what we can do is look at how healthcare works or rather, how it doesn’t in these parts of the city.

This article digs into that reality. The triple barrier of tight, unhygienic living spaces, deep-rooted social stigma, and broken healthcare systems that keeps slum dwellers away from the timely, quality healthcare they deserve. Let’s get into it.

The Challenge of Space

First, let’s start with what a normal day looks like in these slum clusters? Overcrowding! And It’s not about a cramped metro ride or a busy market street. I’m talking about entire families squeezed into single-room homes, dozens sharing one public toilet, and narrow lanes where even daylight struggles to pass through.

And you know what this leads to? Rapid disease transmission. TB, respiratory infections, dengue, and waterborne diseases are things that are an occasional worry for us but a constant, lived reality for them. Speaking of waterborne diseases, it makes me wonder, do they even have access to clean water in the first place?

A report from Mumbai’s slums shows that the average water supply is just 5.37 hours a day. Imagine planning your entire life around those few hours, lining up with buckets, and still not being sure if the water you get is safe enough to drink.

Sanitation is another battle altogether. Limited toilets, broken sewage systems, open drains, and no safe chambers. Hygiene isn’t a choice here, it’s a privilege. And the impact isn’t just physical.

Privacy is almost non-existent. This has a huge, often overlooked consequence that women and adolescent girls avoid seeking medical help. Whether it’s a menstrual health issue, a gynae problem, or even a minor infection, the absence of safe, private spaces means most issues go unchecked, growing quietly in the background.

When it comes to childbirth, it gets worse. There’s a severe lack of safe birthing spaces and immunization centers for newborns. Many are forced to give birth in unsafe, unhygienic conditions, with both mother and child left vulnerable to complications.

And while we’re on health, let’s not ignore what this environment does to mental health. Constant noise, zero personal space, poor sanitation, and the pressure of surviving every day create a toxic environment.

A study in Gujarat showed that 62.5% of older adults in urban slums suffer from multimorbidity, meaning two or more chronic health conditions at the same time. And what makes it worse? Poor health literacy and lack of social support. Basically, people don’t just suffer; they suffer alone, without knowing what’s happening to them or how to get help.

This is what the lack of physical infrastructure does. It’s not just about a leaky roof or a narrow alley; it’s about how it quietly eats away at the body, mind, and dignity of people living there.

There’s this deep-rooted social prejudice against slum communities. It comes not just from the outside world from healthcare providers, officials, and well-off city dwellers but also exists within these communities themselves. Sadly, certain illnesses and conditions are treated like a character flaw rather than a health issue.

Take communicable diseases like HIV/AIDS and TB. The stigma attached to them is so heavy that people avoid getting tested, let alone treated. It’s not just about the fear of death, it’s the fear of being labelled. Of being whispered about, avoided, or worse, isolated.

Reproductive health is no different. A young girl facing menstrual issues or a woman dealing with an unwanted pregnancy often suffers in silence because talking about these things is ‘shameful’. So, small problems turn into serious ones. And we wonder why maternal mortality rates in slums are still high.

Then there’s mental health, something no one wants to talk about. Anxiety, depression, trauma, substance abuse, it’s all there, hidden under the surface. But because there’s so much misinformation and shame attached, people either deny it or drown it out in alcohol or drugs. No one wants to be called ‘paagal’ or ‘weak’. And guess what? Mental health services are almost non-existent here anyway.

So, between judgment, ignorance, and silence, stigma becomes heavier than the actual disease. It isolates people. It delays treatment. And it slowly chips away at whatever little health support system there is.

In slums, stigma is heavier than the disease itself.

Systemic Failures

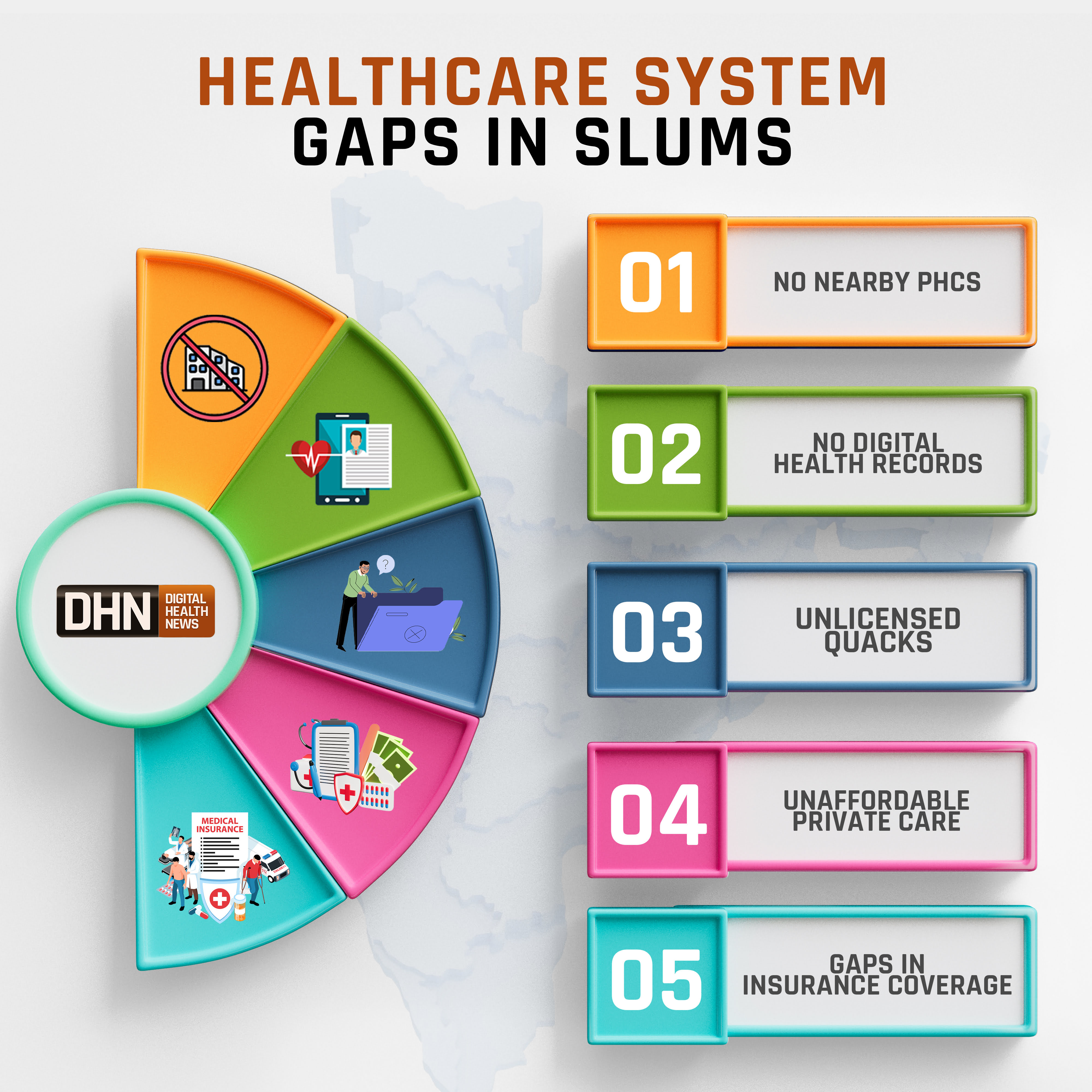

Even if someone manages to get past cramped homes and the weight of social stigma, what they find is a healthcare setup that barely reaches them. The system is supposed to step in when everything else fails, but often ends up failing people even harder.

Primary healthcare centers are either missing from slum pockets or too far away to matter. The ones that do exist are usually overcrowded, under-equipped, and stretched beyond capacity. When a child’s running a high fever at midnight or an elderly person’s breath starts to falter, waiting for a clinic to open in the morning isn’t an option.

With government services unreliable and private hospitals priced out of reach, people are often left with no choice but to turn to whoever’s available. And that often means unlicensed, self-proclaimed doctors with a box of painkillers, a bottle of glucose, and no medical degree in sight.

Emergency transport? Rarely available. Access to specialists? Almost unheard of. And health insurance schemes, while great on paper, are riddled with gaps. Many don’t qualify, some don’t even know about them, and those who do often get lost in a maze of paperwork and petty corruption.

The result? A broken, patchy system where survival depends more on luck and jugaad than any real healthcare infrastructure.

Emerging Solutions & Innovations

Amidst this chaos, there are some stories of hope. Tiny sparks that show what’s possible when people stop waiting for the system and start fixing things on their own, or when someone decides to actually listen.

Mobile health vans are one such lifesaver. These vans roll into slum areas bringing doctors, nurses, and basic medicines right to people’s doorsteps. No long waits, no begging for transport, and no hospital bureaucracy.

Then comes telemedicine. With internet slowly creeping into every corner, a few pilot projects have made it possible for people in slums to consult doctors over video calls. Although network and tech issues are real but it’s a start. Especially for things like mental health counselling or follow-up check-ups.

We also have our ASHAs (Accredited Social Health Activists) and Urban Health Centres (UHCs) who continue to do the job of reaching the unreached. From immunizing kids to busting myths around periods and TB, these women are the backbone of community healthcare where no one else bothers to go.

Digital awareness drives and community workshops have picked up too. Places in Delhi and Mumbai’s slums have seen groups of young volunteers debunking health myths, talking openly about HIV, contraception, and mental health. That invisible wall of shame is starting to crack, slowly.

And when public-private partnerships step in, things move faster. In a few slums of Chennai, tie-ups between NGOs, corporate CSR funds, and local authorities have brought in better sanitation units, mobile clinics, and even small diagnostic labs. When everyone works together, it actually works.

The Way Forward

Several NGOs have been doing important work in these areas for years. But the real question is why should the responsibility stop there? Why isn’t urban slum health a central focus for both public systems and private healthcare giants alike? What if corporate hospitals and medical colleges ran regular outreach programs, mobile clinics, or health camps in these pockets? If permanent healthcare centers aren’t feasible everywhere right now, setting up well-equipped temporary facilities or mobile units could still bridge critical gaps.

It’s time to pull urban slum health out of the margins and place it firmly within mainstream healthcare planning. This isn’t just about building more clinics, it’s about better urban planning, anti-stigma campaigns, and holding systems accountable for the people they routinely overlook.

Most importantly, communities living in these settlements need to have a voice in how their healthcare is designed. Training local volunteers, educating families about preventive care, and building participatory models can transform the way health services operate in these spaces.

At a policy level, this means earmarking dedicated budgets for urban slum healthcare, rolling out portable digital health IDs, and creating incentives for qualified medical professionals to actively serve these communities. Because until healthcare is treated as a basic right, not a privilege defined by where you live, we’ll continue failing the very people who need it most.

Conclusion

India’s ambition of universal health coverage will remain incomplete if its urban poor continue to be overlooked. Breaking down the barriers of space, stigma, and broken systems isn’t just about ticking off a public health goal, it’s about doing what’s right.

Health equity in our cities can’t be real until every slum lane, every cramped home, and every ignored community is part of the plan.

The journey towards health equity in India is far from over, but each digital tool, policy reform, and awareness drive brings us a little closer. To spotlight this critical issue, it is a key theme at DHN Forum Delhi on June 7th, 2025, where top healthcare leaders and innovators will convene to drive meaningful change.

Join us in the conversation—register now!