Where Is All the Health Funding Going?

A Deep Dive into India’s 2025–26 Demand for Grants and the Policy Priorities it Reveals.

When the Union Budget 2025–26 was tabled, one figure immediately caught attention: INR 99,859 crore allocated to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW). The announcement was met with applause in certain circles, given that the allocation represented an 11% increase from the revised estimates of the previous year. For a country with a rapidly growing population, persistent disease burdens, and the dual challenge of communicable and non-communicable illnesses, such an increase seemed, at first glance, a welcome sign of renewed commitment.

However, a budget story is rarely told in a single headline number. The figure is an entry point to a far more complex narrative about priorities, distribution, and long-term vision. Behind the increase lie critical questions: Which sectors will benefit the most? Which health programmes will see modest gains, and which will stagnate? How do these allocations align with India’s stated health policy goals? And perhaps most importantly, will this budgetary expansion translate into better health outcomes for the people it is meant to serve?

This budget, like others before it, is not simply an accounting exercise but a reflection of choices. It reveals how the government intends to balance the competing demands of curative and preventive care, how it weighs the urgency of infrastructure expansion against the quieter but vital work of primary care delivery, and how it positions insurance-based healthcare about public health service provision. Understanding these choices requires more than reading the budget line by line—it calls for interpreting the narrative embedded within the allocations.

Budget in Context: The 2.5% GDP Target and the Reality

In 2017, the National Health Policy (NHP) laid down a measurable and time-bound goal: India’s public health expenditure should reach 2.5% of GDP by 2025. This was not a symbolic target—it was designed to bring the country’s health investment closer to levels seen in comparable economies and to provide the foundation for universal health coverage. However, as the calendar turns to 2025, the numbers tell a sobering story. Combined central and state health spending still hovers at about 1.8% of GDP, short of the policy’s benchmark.

This gap matters. The World Health Organization has long recommended a minimum public health expenditure threshold for countries to provide essential services without catastrophic costs to individuals. India’s current per capita spending remains lower than that of many nations with similar or smaller economies. The consequences are visible: health centres without basic staff, essential drugs running out before the month ends, and patients forced to rely on expensive private care for common illnesses. Out-of-pocket spending remains stubbornly high, at around 48% of total health expenditure, meaning millions risk financial distress each year simply by falling ill.

The challenge, then, is not only how much is allocated in this year’s budget but also whether the trajectory of health financing is moving decisively toward the long-promised target, or whether the gap will remain a structural feature of India’s health system.

Where the Rupees Flow: Allocation Patterns in 2025–26

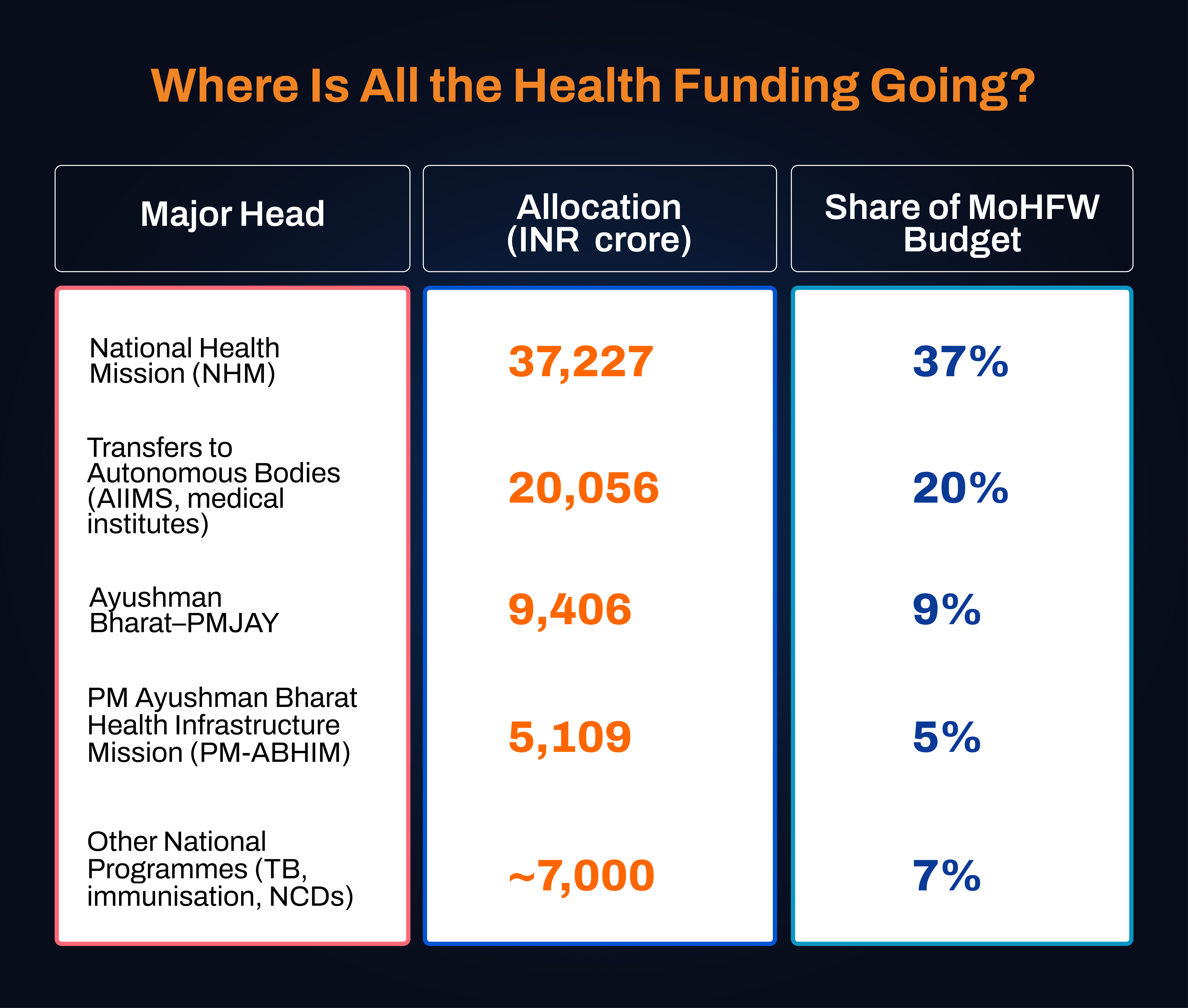

Looking beyond the total figure, the 2025–26 Demand for Grants shows a familiar pattern in how funds are distributed:

More than 60% of the health ministry’s budget is concentrated in three areas: the National Health Mission, the Ayushman Bharat–PMJAY insurance scheme, and funding to autonomous bodies such as AIIMS. This leaves a smaller portion for targeted disease control programmes, preventive health initiatives, and state-level system strengthening.

These proportions are telling. They suggest a continued emphasis on tertiary care facilities and insurance coverage, with less relative emphasis on primary and preventive care. This pattern has shaped India’s health spending for several years.

The National Health Mission: Sustaining the Backbone

The National Health Mission (NHM) remains the most significant component of the health ministry’s budget, at INR 37,227 crore. Since its inception in 2005, NHM has been the backbone of rural health service delivery, financing everything from maternal and child health to disease control and rural health infrastructure. However, this year’s 3.4% year-on-year increase is modest, barely keeping pace with inflation in the healthcare sector.

Any slowdown in growth has tangible consequences for states heavily dependent on NHM funding, particularly in northern and eastern India. Delays in fund disbursal, often reported by state officials, can interrupt services ranging from immunisation drives to the functioning of primary health centres. In states like Bihar and Jharkhand, where state health budgets are already constrained, NHM allocations form a lifeline. When these allocations stagnate in real terms, the impact is immediate and visible at the ground level.

Insurance Expansion: The Ayushman Bharat–PMJAY Model

Over recent years, the Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Aarogya Yojana (PMJAY) has become a central pillar of India’s health financing model. With an INR 9,406 crore allocation, a 24% increase from the previous year—the scheme’s coverage is being widened to include gig workers and informal sector employees, aiming to reduce financial barriers to hospital care.

However, PMJAY covers secondary and tertiary care only, providing financial support once patients are already ill enough to require hospitalisation. Preventive care, outpatient consultations, and early-stage interventions fall outside its scope. The benefits remain underutilized in rural areas, where empanelled hospitals are scarce. This raises a structural concern: if public funds are increasingly channelled into post-illness care without parallel investment in keeping people healthy, the system risks perpetually chasing disease rather than preventing it.

Medical Education and AIIMS Funding

Funding to autonomous institutions—largely AIIMS campuses and new medical colleges—totals INR 20,056 crore. Expanding the medical education pipeline is seen as a long-term solution to India’s human resource gap. This year’s budget outlines 10,000 new MBBS seats for 2025–26, to add 75,000 over the next five years.

While this is a significant capacity boost, distribution challenges remain. Many new colleges are located in urban areas or politically strategic districts, while remote regions with acute shortages wait for dedicated facilities. Faculty shortages and incomplete infrastructure at newer AIIMS campuses have slowed their operational rollout. Without ensuring balanced geographic distribution and adequate staffing, these investments risk concentrating excellence in select hubs rather than strengthening the system nationwide.

The PM Ayushman Bharat Health Infrastructure Mission

The PM Ayushman Bharat Health Infrastructure Mission (PM-ABHIM) has been allocated INR 5,109 crore this year—a 43% increase from the previous budget. The mission focuses on expanding district-level critical care facilities, strengthening disease surveillance, and upgrading diagnostic laboratories.

However, utilisation rates have been a concern. In 2022–23, only around 35% of allocated funds were spent. Although utilisation improved to 90% in 2023–24, much of this occurred in the last quarter of the financial year—a pattern that raises questions about procurement efficiency and planning. Higher allocations can only translate into improved health infrastructure if accompanied by streamlined administrative processes and timely execution.

Ayushman Aarogya Mandirs: Expanding Primary Care Access

The transformation of 1.75 lakh health facilities into Ayushman Aarogya Mandirs marks an ambitious attempt to bring comprehensive primary care closer to communities. These centres aim to provide services beyond basic curative care, including NCD screenings, mental health support, and diagnostic facilities.

However, reports from various states indicate that many of these centres continue to struggle with shortages of doctors, nurses, and laboratory technicians. Drug supplies are inconsistent, and diagnostic services often face interruptions. In some cases, patients screened for chronic conditions are left without accessible follow-up care. Without parallel investments in staffing, supply chains, and clinical pathways, these facilities risk becoming symbolic rebrandings rather than functional upgrades.

Non-Communicable Diseases: The Rising Burden

India’s disease profile has shifted significantly over the past three decades. In 1990, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) accounted for 38% of all deaths; by 2023, that figure had risen to 62%. This epidemiological shift demands a reorientation of public health priorities.

Despite this, funding for NCD programmes remains a small share of the total, around 3% of NHM spending as of 2020–21. While screening initiatives for conditions like diabetes and hypertension have expanded, they often suffer from patchy coverage and inadequate follow-up care. Without sustained investment, the rising tide of NCDs threatens to overwhelm health services and increase long-term treatment costs.

Communicable Diseases: Maintaining the Gains

India has made substantial progress in controlling communicable diseases, particularly vaccine-preventable illnesses. However, the challenge is far from over. Tuberculosis continues to claim over 400,000 lives annually, and immunisation coverage remains uneven, especially in certain northeastern states. Vector-borne diseases also continue to pose seasonal risks.

In the 2025–26 budget, allocations for communicable disease programmes remain under 10% of the total MoHFW outlay. While this may reflect confidence in existing control measures, it also leaves these programmes vulnerable should new outbreaks emerge.

State-Level Health Spending

The Health Cess and its Allocation

The health and education cess, levied at 4% on income tax, is designed to allocate 25% of its proceeds to health through the Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Nidhi. 2025–26, however, only 19% of expected collections will be directed to health. Oversight bodies have noted this shortfall, which raises questions about the transparency and predictability of earmarked funding.

Conclusion: Aligning Allocations with Outcomes

Budgets are not only financial instruments; they reflect policy priorities. The 2025–26 health budget prioritises expanding tertiary care capacity, growing insurance coverage, and building medical education infrastructure. Yet preventive and primary care, which are critical to reducing disease burdens in the first place, receive less emphasis.

The central question is whether the current spending balance will be sufficient to meet immediate health service demands and the long-term goal of universal health coverage. For now, the budget offers increased resources and some promising initiatives. Still, the path to stronger health outcomes will depend on whether these funds are spent efficiently, equitably, and with a sustained focus on the foundational elements of public health.

The success of central health schemes depends heavily on state-level investment. The NHP recommends that states allocate 8% of their budgets to health; most fall short, averaging around 6%. Some states, including economically stronger ones, spend even less.

This creates a paradox: poorer states with greater health needs often have fewer resources to invest, and NHM allocations do not always compensate for this gap. As a result, the regions most needing strengthened health systems may be the slowest to achieve them.